Introduction

A pre-trained large language model (PLM), also known as a foundational model, is trained in an unsupervised manner on massive volumes of text data. These models exhibit a strong ability to understand natural language structure and semantics. However, in their base form, they are not directly suitable for downstream tasks. For instance, a decoder-only LLM (e.g GPT3.5), pre-trained on vast amounts of text, is primarily designed to predict the next word in a sequence. Similarly, an encoder-only LLM (e.g BERT) can interpret input text and generate context-based word embeddings, but it cannot perform complex tasks like question answering or summarization without further adaptation.

To bridge this gap, there are two key strategies for leveraging pre-trained LLMs for downstream tasks: fine-tuning and few-shot learning. Fine-tuning involves adapting the model to a specific task by training it on task-specific data, while few-shot learning leverages the model’s inherent capabilities to perform tasks with minimal examples or prompts. In this post, we will briefly explore both approaches, highlighting their benefits, challenges, and use cases.

Fine-Tuning

Fine-tuning pre-trained LLMs is a common approach for adapting these models to specific downstream tasks. This approach involves taking a pre-trained model and further training it on a task-specific dataset, allowing the model’s weights to be updated in order to minimize a specific loss function for the target task. This process enables the model to specialize in the target task while retaining the general language understanding acquired during pre-training. For example, BERT achieves state-of-the-art performance in tasks such as text classification and question answering after fine-tuning on task-specific datasets.

Fine-tuning typically requires a substantial amount of labeled data for the target task. Fine-tuning on small, task-specific datasets can lead to overfitting, where the model performs well on the training data but poorly on unseen data. In domains where labeled data is scarce, this can be a significant limitation. Another problem is catastrophic forgetting when fine-tuning, there is a risk that the model may “forget” some of the general knowledge it learned during pre-training. This can be particularly problematic in multi-task learning scenarios.

Additionally, due to the vast number of parameters in large language models, fine-tuning these models requires significant computational resources, including high-performance GPUs or TPUs. These limitations can make fine-tuning LLMs costly and impractical for many researchers and organizations. Consequently, there is an increasing need for more efficient and cost-effective solutions. Recently, parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, such as LoRA, have been developed to reduce computational costs while maintaining performance.

In conclusion, fine-tuning has proven to be an effective method for leveraging the power of pre-trained LLMs across a wide range of natural language processing (NLP) tasks. But it also comes with challenges such as data requirements, overfitting, catastrophic forgetting, and computational costs.

In the next section, we will explore the alternative strategy of few-shot learning, including prompt engineering and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and how it compares to fine-tuning in terms of effectiveness and efficiency.

Few-Shot Learning

While fine-tuning is a powerful approach for adapting LLMs to downstream tasks, it is not always the most practical or efficient solution, especially when labeled data is scarce or computational resources are limited. In such scenarios, few-shot learning emerges as a compelling alternative. Few-shot learning leverages the inherent capabilities of pre-trained LLMs to perform tasks with minimal task-specific data. In fact, It’s because the few-shot capabilities of LLMs that we can leverage prompt-engeering and RAG. Let’s discuss these two strategies.

Prompt Engineering

Prompt engineering is a powerful and increasingly popular method for leveraging pre-trained LLMs in downstream tasks without the need to modify the model’s weights. Instead of fine-tuning the model on task-specific data, prompt engineering involves designing input prompts that guide the model to produce the desired output. During unsupervised pre-training, an LLM develops a wide range of skills and pattern recognition abilities. It then utilizes these capabilities during inference to quickly adapt or identify the target task, a capability known as in-context learning [1]. This approach is particularly useful in few-shot and zero-shot learning scenarios, where labeled data is scarce or unavailable. By employing prompt engineering, the inherent capabilities of pre-trained models can be effectively harnessed to achieve desirable outcomes.

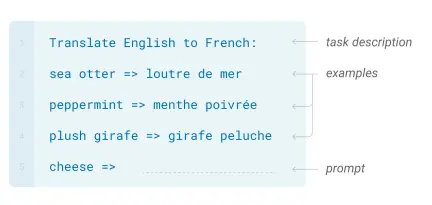

For example GPT3 can do translation in a few-shot manner:

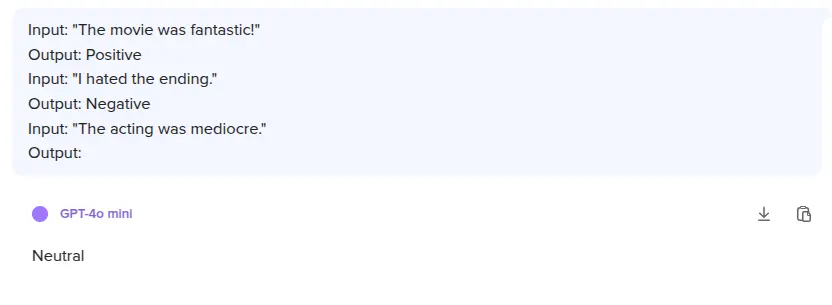

As an another example, we can do sentiment-analyis by using LLM existing knowlege and reasoning capabilities to perform tasks with only a few examples or instructions:

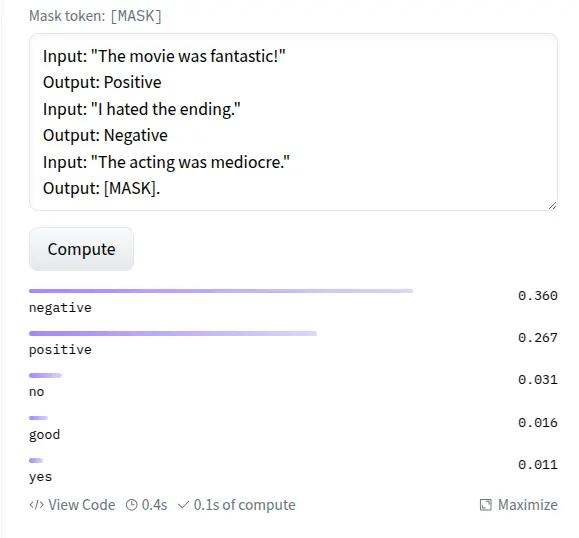

We can also use BERT for this scenario:

We can see that the output is diffrent based on the model in hand. The two important factors of an LLM few-shot capabilites are model size and quality and design of the prompt.

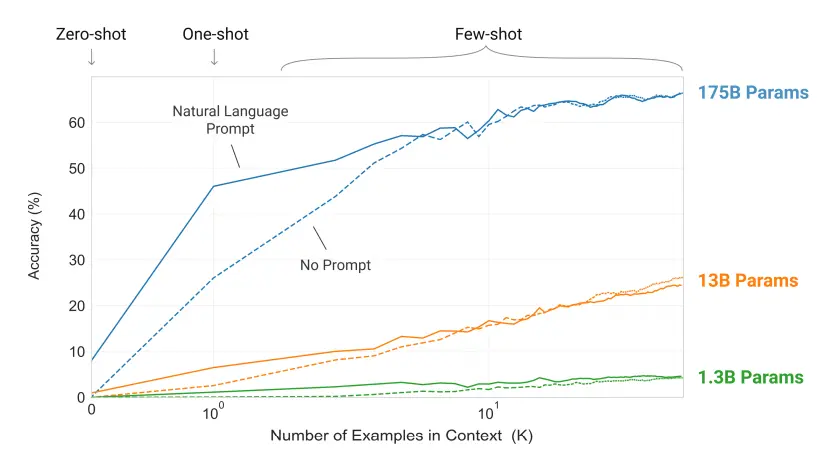

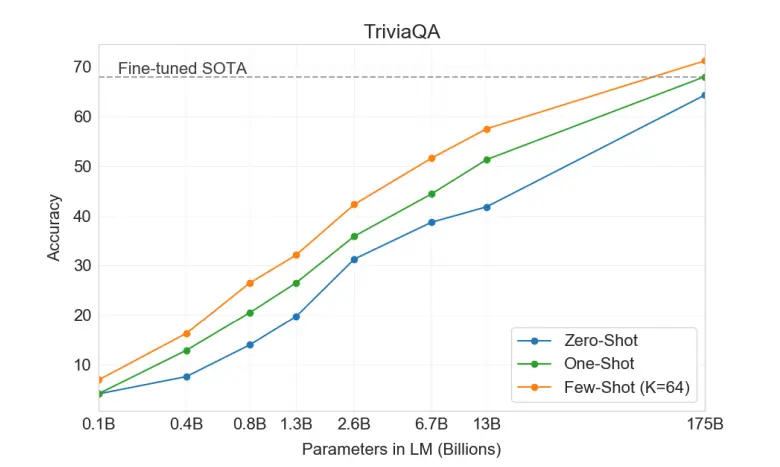

For model size, the rule of thumb is that bigger is generally better. This concept is examined comprehensively in the paper Language Models are Few-Shot Learners.

We can observe that smaller models perform poorly in few-shot scenarios. For instance, a small model like BERT (with 110 million parameters) is not suitable for performing downstream tasks in a few-shot manner. In contrast, larger models like GPT-3 (with 175 billion parameters) are well-suited for these scenarios and can handle a wide variety of tasks with just prompt-engineering, without the need for any fine-tuning, thanks to their few-shot capabilities.

Prompt engineering offers several benefits, including minimal data requirements, as it can achieve reasonable performance with few or even zero examples, and it does not make any updates to the model, making it computationally efficient without additional fine-tuning. This approach enables rapid prototyping, allowing for quick experimentation and deployment, which is particularly advantageous when time and resources are constrained.

However, it also presents challenges, first it requiers a large model (at least with 7 billion paramters) to perform with good accuracy and second the effectiveness heavily relies on the quality of the prompts, with poorly crafted ones potentially leading to suboptimal results. Furthermore, there is limited control over the model’s generalization to new tasks since its parameters remain unchanged, and for complex tasks, prompt engineering may face scalability issues, struggling to match the performance of fine-tuned models, especially when specific task nuances are involved.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

LLMs have inherent limitations, such as hallucinations and outdated internal knowledge. Pre-trained LLMs store factual knowledge within their parameters, leading to very good results when fine-tuned on downstream tasks. However, LLMs are not capable of accurately retrieving and documenting facts and often suffer from hallucinations. For example, a pre-trained large language model might respond to the question, “Who is the President of the United States in February 2025?” with, “In February 2025, Joe Biden is the President of the United States.” Such errors arise from probabilistic retrieval and the model’s outdated knowledge. We can’t fine-tuning the LLM each time the data changes, because it will be very costly and time-consuming.

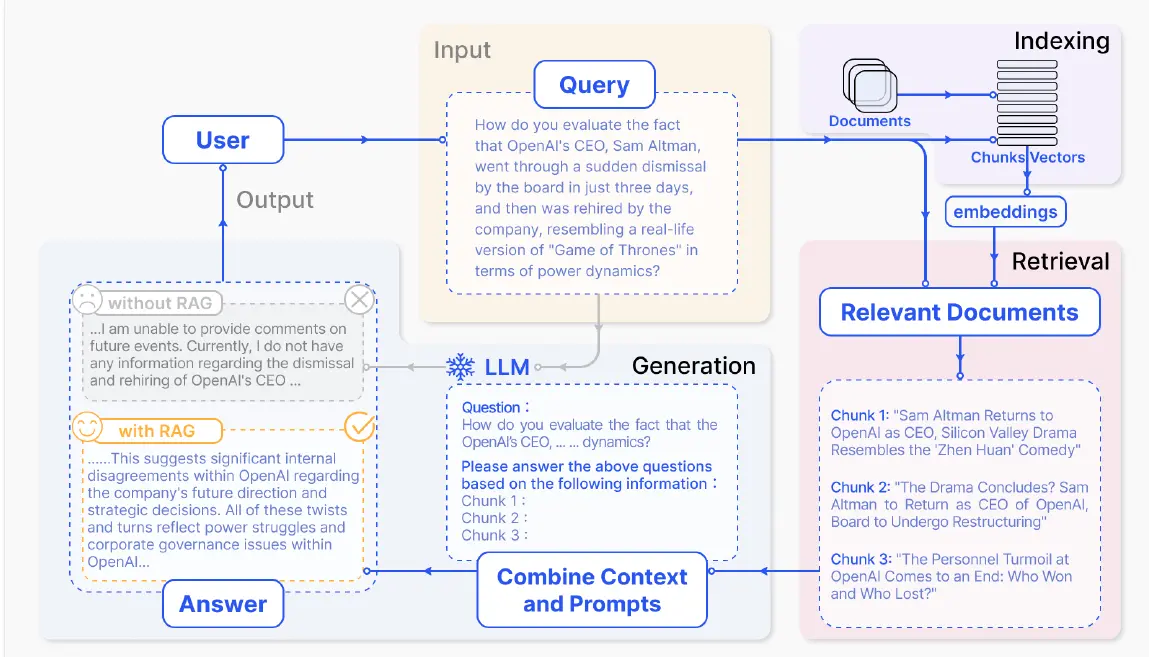

RAG is an effective solution to these limitations. This technique allows the system to leverage existing domain-specific text data repositories to supplement the knowledge of the language model, thereby providing more accurate responses and reducing hallucinations

RAG combines retrieval-based methods with generative models. In RAG, a retriever first fetches relevant documents from an external knowledge base, which are then used by a generative model to produce responses. This approach enhances the model’s ability to generate accurate and contextually relevant answers, particularly for knowledge-intensive tasks such as question answering and fact-checking. RAG can be seen as an extension of in-context learning, where the context is dynamically retrieved from external sources rather than being explicitly provided in the prompt. By integrating retrieval with the generative and comprehension capabilities of large language models, RAG addresses key limitations of traditional large language models, which include reliance on static knowledge and vulnerability to generating incorrect or outdated information.

RAG allows the model to access up-to-date or domain-specific information that may not be present in its pre-trained knowledge base. By grounding responses in retrieved evidence, RAG can produce more accurate and factually consistent outputs, especially for knowledge-intensive tasks like open-domain question answering. Also, RAG can handle tasks that require access to large or dynamic knowledge bases without the need for extensive fine-tuning.

The effectiveness of RAG depends heavily on the quality of the retrieval system. Poor retrieval can lead to irrelevant or noisy context, degrading the model’s performance. Also the retrieval step may add additional computational cost, which can make RAG slower compared to pure prompt-engineering or fine-tuning.

Conclusion

Two primary strategies for leveraging LLMs are fine-tuning and few-shot learning, each with its own strengths and ideal use cases. Fine-tuning excels when abundant labeled data is available, enabling deep task-specific adaptation and high performance, though it requires significant computational resources and carries risks like overfitting. On the other hand, few-shot learning, including prompt engineering and RAG, is highly effective in low-resource scenarios, offering flexibility, rapid deployment, and the ability to incorporate external knowledge without modifying the model’s parameters.

The choice between these approaches depends on factors like data availability, task complexity, and resource constraints. Fine-tuning is well-suited for domain-specific tasks requiring high precision, while few-shot learning shines in general-purpose applications or when quick adaptation is needed. As LLMs continue to advance, hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both strategies are likely to emerge, further enhancing their effectiveness. By understanding the nuances of fine-tuning and few-shot learning, we can harness the full potential of LLMs to drive innovation and solve real-world challenges more effectively.

References

[1] T. Brown et al., “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Dec. 2020.

[2] Y. Gao et al., Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey, arXiv:2312.10997, Ongoing Work, Dec 2023.